Crystal Clear: A Comparative Analysis of Crystal in Eastern and Western Cultural Applications

Introduction: From Geological Marvel to Cultural Icon

Across the tapestry of human civilization, few natural substances have captivated the imagination as profoundly as crystal. Beyond its scientific identity as quartz, its geometric perfection and luminous clarity have made it a powerful vessel for cultural meaning, a canvas onto which societies project their deepest beliefs about the world. For millennia, this geological marvel has been transformed into a cultural icon, cherished not just for what it is, but for what it represents.

This article conducts a comparative analysis of the historical origins, symbolic meanings, and practical applications of crystals. It contrasts the aesthetic and medicinal traditions of the East, primarily rooted in Chinese history, with the metaphysical and energetic frameworks that have become prevalent in the West. By examining how these two cultural spheres have perceived, named, shaped, and utilized the same material, we uncover a fascinating story of divergent worldviews.

This exploration reveals distinct yet occasionally overlapping perspectives on health, spirituality, and the intricate relationship between humanity and the natural world. From a tangible ingredient in ancient pharmacopoeias to an intangible conduit for cosmic energy, the journey of the crystal through Eastern and Western cultures is a clear reflection of the values they hold most dear.

1. Foundations: Historical Perceptions and Ancient Naming Conventions

The names and earliest recorded uses of a material within a culture provide fundamental insight into its philosophical and spiritual worldview. These initial perceptions establish the foundation upon which all subsequent applications—be they artistic, medicinal, or spiritual—are built. In the case of crystal, its ancient nomenclature in both the East and West reveals the core qualities that each civilization found most compelling.

The Essence of Water and Spirit: Crystal in Ancient China

The ancient Chinese nomenclature for crystal reveals a worldview deeply embedded in elemental philosophy, framing the stone as a pure, primordial substance. The most significant of these names was 水精 (shuǐ jīng), meaning "essence of water." This term stemmed from the profound belief that crystal was a form of thousand-year-old ice that would never melt, a substance that had achieved a state of perfect, eternal purity. This connection to the elements is echoed in other historical names, such as 水玉 (shuǐ yù, "water jade"), which not only reinforced its association with water but also elevated it to the status of jade, the most revered material in Chinese culture. With the arrival of Buddhism, crystal also became known as 菩萨石 (púsà shí, "Bodhisattva stone"), linking its clarity to spiritual enlightenment and compassion. The stone's cultural significance is woven into the very fabric of Chinese literary history, with mentions in classical texts like the 山海经 (Classic of Mountains and Seas) and frequent appearances in ancient poetry, where it evokes images of clarity, purity, and ethereal beauty.

Talismans of Power and Portents: Crystal in the Ancient West

In the ancient West, the perception of crystal was rooted less in elemental philosophy and more in its application as a tool of power, protection, and insight. Early civilizations harnessed it as a talisman to influence fortune and ward off harm. In Ancient Greece, amethyst was worn as a prophylactic against drunkenness, while Roman legions carried crystal talismans into battle, believing they offered divine protection. Beyond its role as a protective amulet, crystal was a primary medium for esoteric practices. The Druids, the high-ranking professional class in ancient Celtic cultures, utilized it in religious ceremonies. It was also central to the art of scrying, where seers would gaze into a polished crystal sphere to divine the future and gain hidden knowledge. In these traditions, crystal was valued not for its intrinsic essence but for its perceived ability to channel and reveal unseen forces.

These foundational beliefs—crystal as the essence of purity in the East and as a conduit of power in the West—directly shaped the distinct ways each culture would go on to craft, wear, and utilize this captivating stone.

2. The Art of Adornment: Craftsmanship Versus Fashion

While the use of crystals in personal adornment is a universal practice, the cultural emphasis—whether on the masterful transformation of the raw material or on its symbolic placement on the body—reveals profound differences in aesthetic and cultural values. The East celebrated the artisan's ability to reveal the stone's inner beauty, while the West often focused on the symbolic power conferred upon the wearer.

The Carver's Hand: Crystal as a Medium in Chinese Art

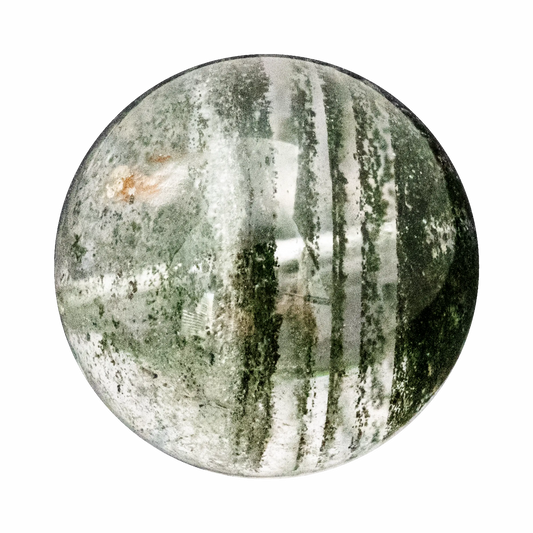

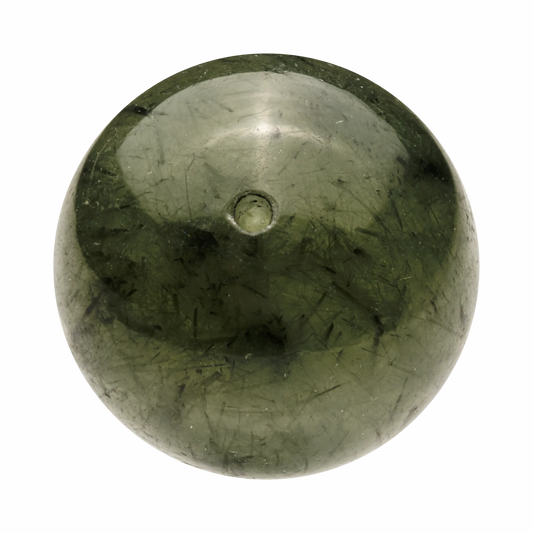

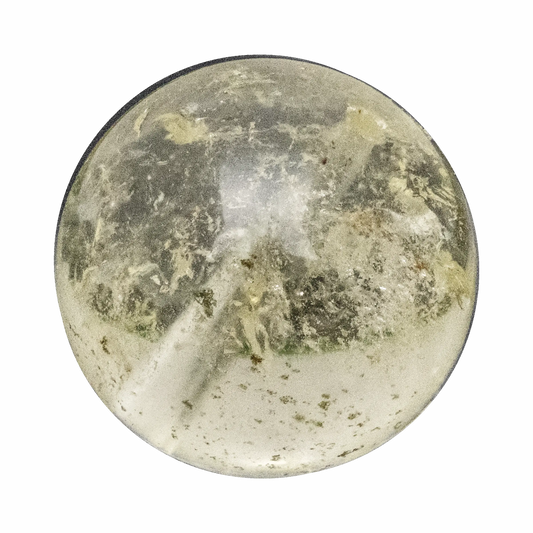

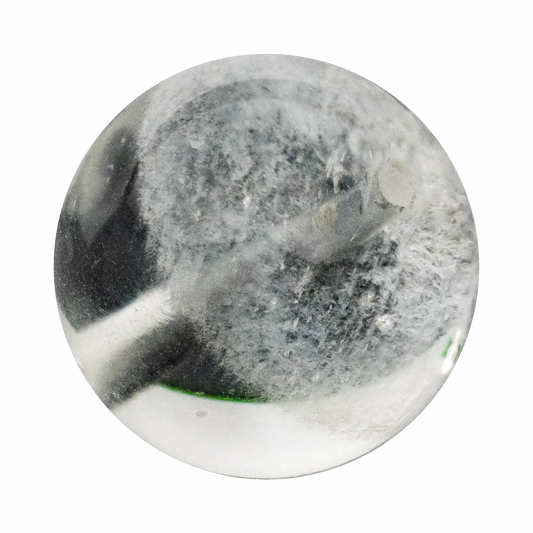

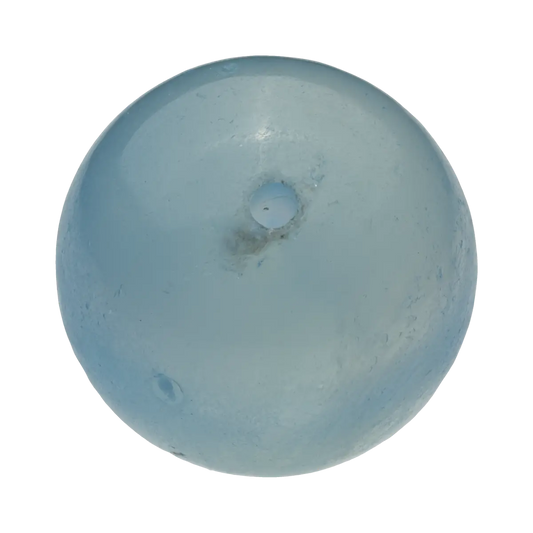

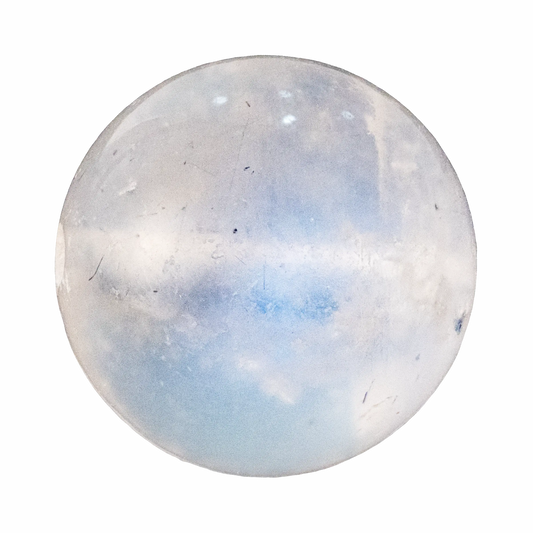

The guiding principle of Chinese crystal artistry is captured in the phrase "七分天然, 三分人工"—"seven parts nature, three parts human effort." This philosophy represents a cultural ethic that prioritizes co-creation with nature over human dominance. The carver's role is not to impose a vision upon the stone but to enhance and reveal the beauty already present within it. This is the logical outcome of a worldview that sees crystal as 水精, the "essence of water," a substance whose inherent purity is to be revered, not conquered. This tradition of masterful craftsmanship has ancient roots, as evidenced by a sophisticated crystal cup from the Warring States period (475–221 BC) unearthed in Hangzhou in October 1990. This mastery was elevated to the realm of the sacred during subsequent dynasties, with discoveries of exquisite crystal Buddhist statues and personal adornments from the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD), including necklaces (水晶项链), pendants (水晶佩饰), and earrings (水晶耳坠). Today, Chinese artisans continue to process high-quality raw crystal into various forms, such as smoothly polished bangles (手镯), brilliant faceted gems (戒面), and perfectly clear spheres (球), with the value intrinsically tied to the purity of the material and the excellence of the craftsmanship.

The Wearer's Choice: Crystal as Symbol in Western Jewelry

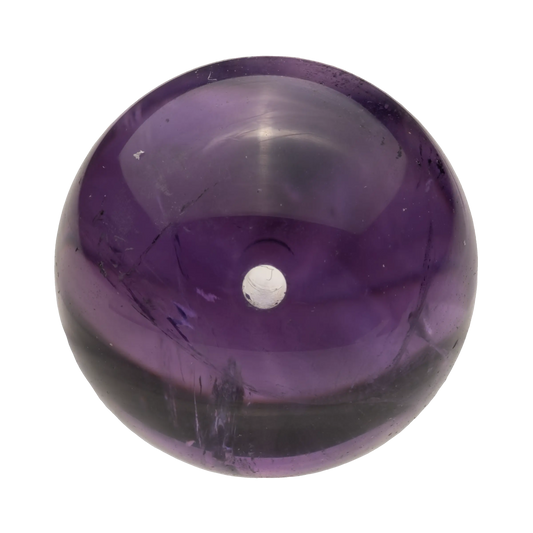

In Europe, the history of crystal adornment is more closely tied to fashion, status, and the symbolic properties attributed to the stones. In the 15th century, both men and women wore crystal necklaces. By the 16th century, the practice had gained royal favor, with Queen Elizabeth I of England being particularly fond of such pieces. This trend continued into the 18th century, where elaborate crystal jewelry became a staple of aristocratic attire, signifying wealth and social standing. While craftsmanship was certainly valued, the Western tradition often placed a greater emphasis on the act of wearing the crystal for its symbolic or protective power. An amethyst necklace, for instance, was worn not just for its beauty but specifically for the protection it was believed to offer. Here, the focus shifts from the object's creation to the benefits it confers upon the individual, making it a personal accessory of power and style.

This divergence in use, celebrating the carver's hand in one culture and the wearer's choice in another, extends beyond aesthetics and into the vital domain of health and well-being.

3. Philosophies of Healing: Material Medicine and Metaphysical Energy

The application of crystals for healing provides the starkest contrast between Eastern and Western traditions, pitting a material, medicinal approach against a metaphysical, energetic one. One tradition integrated crystal into a system of material pharmacology, while the other uses it as an external tool within a broader system of sympathetic magic, where an object's perceived properties can influence a corresponding human state.

The Eastern Approach: Crystal in Traditional Chinese Medicine

Within the comprehensive system of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), crystal was classified as a potent medicinal ingredient—a form of material pharmacology. The renowned Ming Dynasty physician Li Shizhen included crystal in his seminal work, the 本草纲目 (Compendium of Materia Medica), prescribing it to calm the heart (安心), pacify fright (定惊), and, notably, to improve eyesight (明目). This latter property, documented in classical texts, represents a powerful anthropological insight: the conceptual link from crystal as 水精 ("essence of water") to its function in clarifying vision is direct and intuitive. Even earlier texts, such as the 神农本草经 (The Divine Farmer's Materia Medica), attribute crystal with the ability to nourish the five viscera and calm the spirit. In this framework, crystal is a physical medicine, ground into powders or used in compounds to act upon the body's material substance.

The Western Approach: Crystal as a Conduit for Energy

The modern Western concept of crystal healing is predicated on "crystal energy." This belief holds that because crystals possess a precise and stable internal structure, they can absorb, transmit, and amplify energy. This property, it is argued, can be used to interact with and rebalance the human body's own energy field, often referred to as the aura. The healing is not material but metaphysical, operating on a vibrational level. This framework has given rise to a wide array of applications, often tailored to specific needs:

- Overall Well-being: Crystals are used to eliminate negative energy from a person or space, calm turbulent emotions, and stimulate creativity and inspiration.

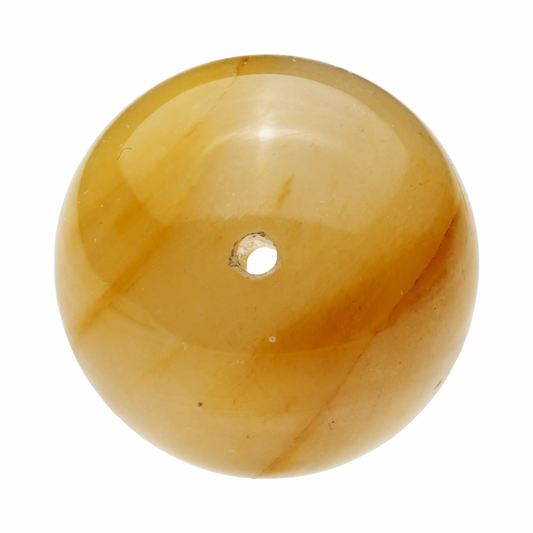

- Emotional Healing: Specific stones are matched to emotional states. For instance, Rose Quartz is widely used to soothe heartache, Amethyst is recommended for stress relief, and Citrine is believed to bolster confidence.

- Physical Ailments: In crystal healing practices, stones are often placed directly on parts of the body to alleviate physical symptoms. Comprehensive guides match specific crystals to illnesses, such as using Bloodstone for anemia or placing Amethyst on the forehead to ease a headache.

These distinct healing philosophies are deeply embedded within the larger metaphysical systems of each culture, extending from personal well-being to broader spiritual applications.

4. Spiritual and Symbolic Realms: Feng Shui, Divination, and Magic

Moving beyond personal healing, crystals are deeply integrated into broader spiritual and symbolic systems that govern humanity's interaction with the wider cosmos. In the East, this often manifests as a quest for harmony and fortune within the material world, while in the West, it frequently involves accessing unseen realms for divination, intuition, and magical practice.

Harmony and Fortune: Crystal in Chinese Symbolism

In modern Chinese culture, different types of crystals are imbued with specific symbolic meanings tied to prosperity, relationships, and success. This symbolism is practical and life-affirming, focused on enhancing one's fortune in the here and now. Citrine (黄水晶) is widely known as the "merchant's stone," believed to attract wealth, while Amethyst (紫水晶) is hailed as the "guardian stone of love." Phantom Quartz (幽灵水晶), with its layered mineral inclusions, is associated with career progression and business success. These symbolic properties find their practical application in Feng Shui, the Chinese art of placement. By strategically positioning a citrine geode in a home or office to enhance wealth, or a piece of rose quartz (粉晶) to attract romance, a symbolic stone becomes a functional tool for shaping one's material environment—a perfect expression of the Eastern approach.

Magic and Intuition: Crystal in Western Metaphysics

In Western esoteric traditions, crystals are treated as active tools for engaging with metaphysical energies and the subconscious mind. Common practices include divination, where the iconic crystal ball is used for scrying to receive visions, and a clear quartz pendulum is used for dowsing to find answers. Crystals are also used to enhance intuition by being placed on the "third eye" to strengthen psychic awareness or to aid in dream recall. Specific stones like Black Tourmaline and Obsidian are believed to create a protective shield against negative energy or "psychic attack." A fascinating point of convergence is the modern focus on specific crystal formations. This vocabulary, largely developed within Western metaphysics, includes specialized forms like Cathedral, Dow, Elestial, and Tantric Twin crystals, each believed to possess a unique function. This esoteric terminology has been adopted into the global crystal lexicon and is now detailed even in Chinese-language guides, demonstrating the cross-pollination of these systems.

Though these spiritual paths began in very different places, the modern era is witnessing a fascinating intersection of these once-distinct belief systems.

5. Conclusion: A Synthesis of Traditions in a Globalized World

The cultural journeys of crystal in the East and West reveal a fundamental dichotomy. The Eastern tradition, rooted in Chinese culture, has historically valued its tangible qualities: its aesthetic beauty perfected by masterful craftsmanship, its physical purity reminiscent of water and ice, and its material properties as a documented ingredient in medicine. In contrast, the Western tradition has overwhelmingly emphasized its intangible qualities: its theoretical energy, its vibrational frequency, and its symbolic power as a tool for metaphysical exploration and psychic enhancement.

In our increasingly interconnected world, however, these once-parallel lines are beginning to converge. This emerging syncretism suggests a global search for meaning where consumers selectively blend traditions—seeking the material authenticity and ancient pedigree of the East while simultaneously adopting the West's personalized, energetic frameworks to navigate modern anxieties. Eastern markets are increasingly adopting Western concepts of "crystal energy," while Western consumers are developing a greater appreciation for the provenance and artistic carving of crystals from regions like Donghai, China.

Ultimately, the enduring power of the crystal lies in its remarkable ability to be both a beautiful object and a blank slate for human meaning. Whether viewed as a key to earthly fortune or a gateway to cosmic consciousness, it remains a powerful cultural artifact that reflects and shapes humanity's deepest questions about nature, beauty, healing, and the unseen forces of the universe.